Quarterly Economic Outlook: Waiting on clarity.

In our last outlook, we expressed growing concern about the intermediate-term outlook for the Canadian economy, given the Trump Administration’s global trade war against a backdrop of slowing domestic economic growth and rising unemployment. We remain concerned, but hard economic data (primarily economic growth, inflation, and unemployment) have yet to deteriorate meaningfully. While that’s encouraging, it’s early days yet and those risks are still clearly in play. This puts businesses, households, economists, central bankers, and investors firmly in wait-and-see mode as we head into the second half of the year.

Anxiety and uncertainty abound

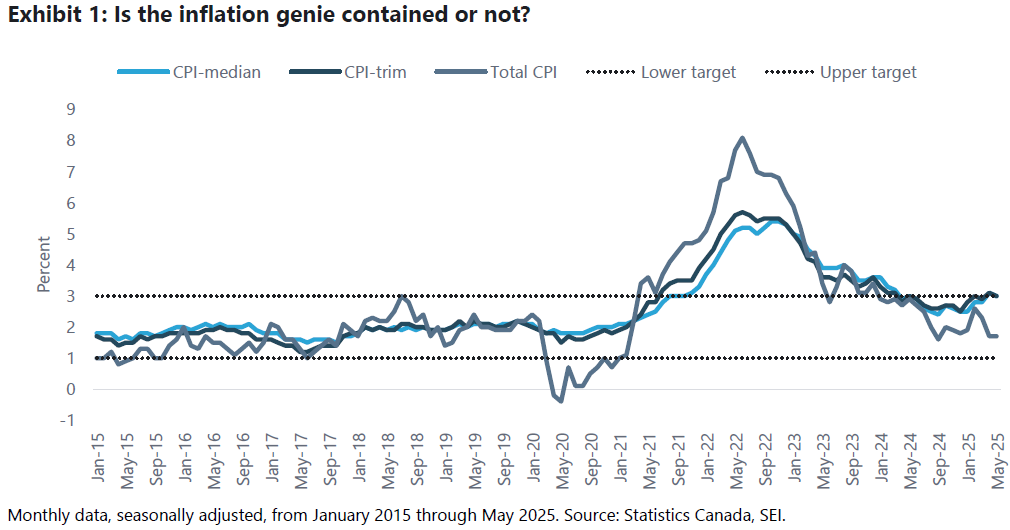

While economic surveys tend to be somewhat unreliable in terms of predicting actual future behavior, it is important to note that both business and household surveys are indicating significant anxiety around U.S. tariffs.1 The Bank of Canada (BOC) is in a similar place. While first-quarter economic growth surprised a bit to the upside and inflation has looked fairly tame, final domestic demand was flat—trade data likely distorted these figures as businesses and consumers tried to get ahead of U.S. tariffs—and the BOC’s preferred measures of inflation remain stubbornly at the high end of its desired range (Exhibit 1).

As the BOC put it following its decision to hold its policy interest rate steady in June, “the outcomes of these [trade] negotiations are highly uncertain, tariff rates are well above their levels at the beginning of 2025, and new trade actions are still being threatened. Uncertainty remains high…The Bank’s preferred measures of core inflation, as well as other measures of underlying inflation, moved up. Recent surveys indicate that households continue to expect that tariffs will raise prices and many businesses say they intend to pass on the costs of higher tariffs. The Bank will be watching all these indicators closely to gauge how inflationary pressures are evolving. With uncertainty about U.S. tariffs still high, the Canadian economy softer but not sharply weaker, and some unexpected firmness in recent inflation data, Governing Council decided to hold the policy rate as we gain more information on U.S. trade policy and its impacts. We will continue to assess the timing and strength of both the downward pressures on inflation from a weaker economy and the upward pressures on inflation from higher costs.”2 This aligns closely with views being expressed by monetary policymakers in some other countries.

Not a lot of hiring or firing

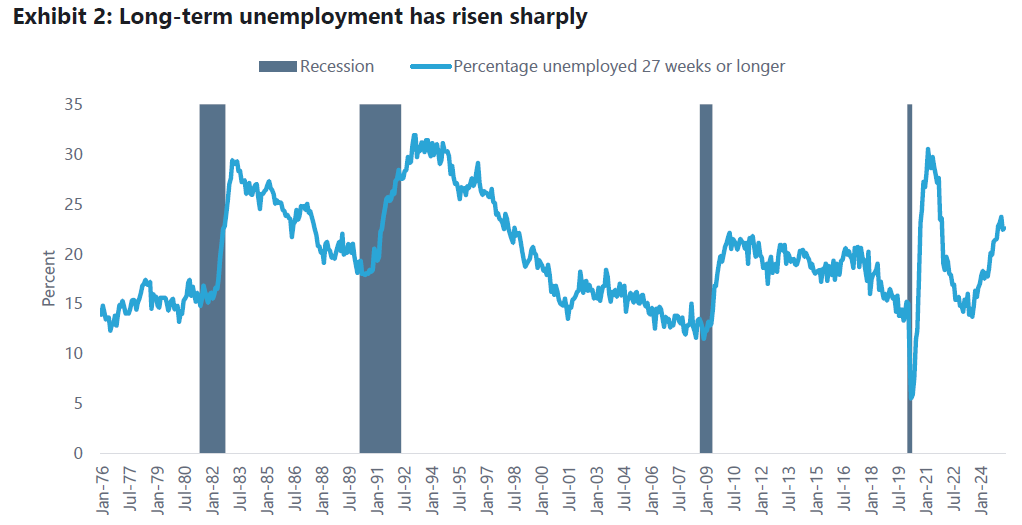

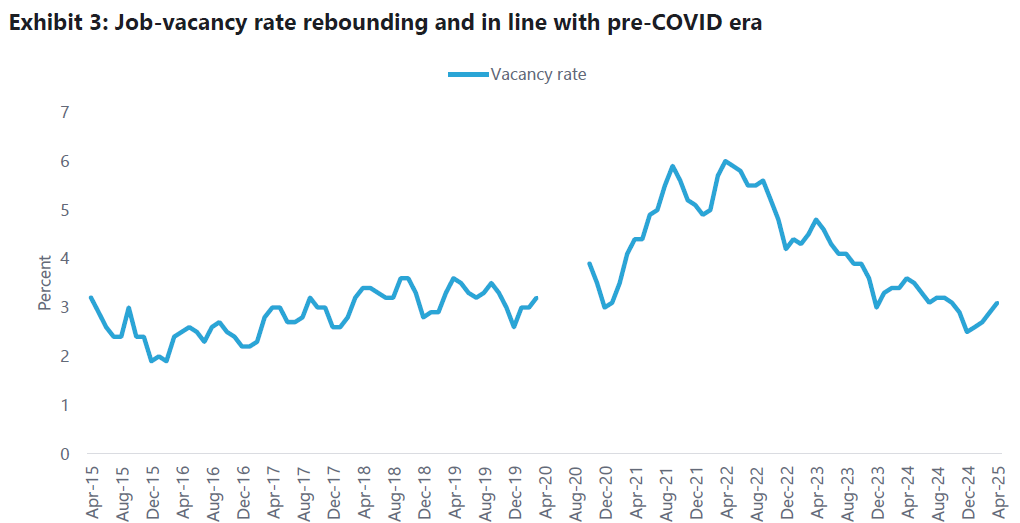

Canada’s labour market is also in a similar spot to many other countries. While there have been clear signs of softening from the strong-labour-demand period that followed the reopenings of national economies after the initial waves of COVID-19, employment conditions in many regions have eased to more normal levels, and labour markets have yet to show signs of significant unravelling. As shown in Exhibits 2 and 3, while the duration of unemployment has been worsening in Canada3, job vacancies have actually increased in three of the first four months of 2025, and the job-vacancy rate has been holding steady at around 3.5%—well below the COVID-19 reopening years of 2021-2022, but in line with historic levels outside that period.

Monthly data, seasonally adjusted, from January 1976 through May 2025. Percentage of unemployed who have been out of work for 27 weeks or longer. Grey bars indicate recession periods as defined by The CD Howe Institute. Source: CD Howe Institute, Statistics Canada, SEI.

Monthly data, seasonally adjusted, from April 2015 through April 2025. No data from April 2020 through September 2020. Vacancy rate is calculated by dividing job vacancies by payroll employees. Source: Statistics Canada, SEI.

While we remain concerned about the trajectory of unemployment, the Canadian economy has managed to avoid recession thus far barring any significant future revisions to economic data. (Official economic growth estimates are revised on a regular schedule but aren’t finalized until nearly three years after the fact4).

Fiscal support on the way?

As with trade policy, there’s still a fair amount of uncertainty around fiscal policy in Canada. The Liberal-led government has released its initial spending plans and “main estimates” of appropriations (also known as the Blue Book), but it doesn’t plan to submit an official budget until this fall. Based on initial figures, there could be a meaningful government spending impulse in 2026, similar to a number of other countries. But the specifics of those spending plans and what they might mean for employment, inflation, and Canada’s longstanding productivity challenge are not yet clear.

Digging into trade flows

In the fog of a trade war, trade flows occupy a more prominent place in economists’ minds. Beyond the obvious concerns about what will ultimately be tariffed and at what rates by the U.S. (and counter-tariffed or taxed by Canada and other countries), it’s interesting to think about how trade flows will adapt to the various measures and countermeasures. We have a couple of observations to offer.

As with the first Trump Administration’s trade policy, there seems to be a common-but-questionable assumption that global trade flows can only adapt haltingly and chaotically to dramatic shifts in tariff schedules. However, like some of the adjustments that occurred in response to the prior Trump Administration’s tariffs, recent theoretical work and trade-flow data seem to indicate otherwise. In a March working paper, a BOC economist argued that, rather than being inelastic or difficult to change, commercial trade behaviors (at least based on the author’s chosen data set) appeared to be highly flexible and adaptable.5 While interesting in its own right, recent Canadian trade data lend support to the argument. According to Statistics Canada (StatCan), Canadian exports to the U.S. declined for a fourth consecutive month in May and now account for roughly 68% of total exports from a monthly average of 76% in 2024. However, total Canadian exports to other countries reached a record high.6

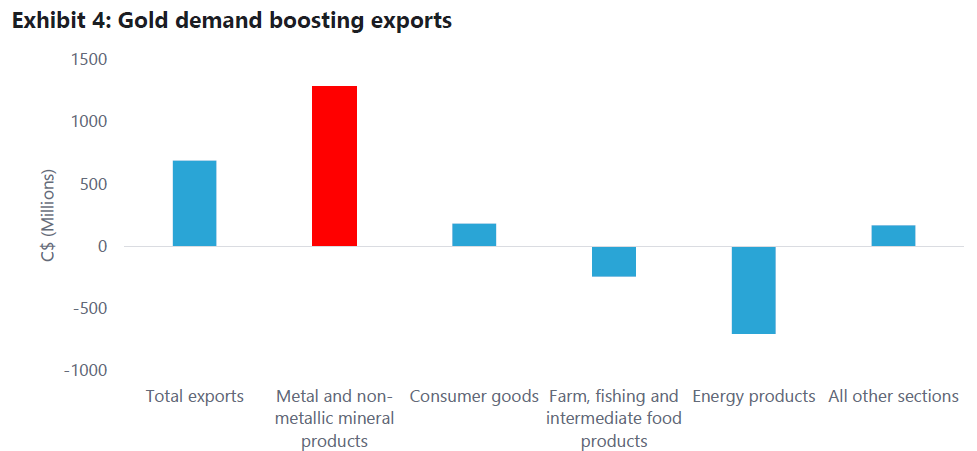

Gold demand adds another interesting wrinkle to the trade data (as well as the longer-term outlook for central bank reserves and the importance of gold and the U.S. dollar in the global financial system). The gold story is fairly well known in financial market circles now—despite traditional gold-price indicators pointing down, demand, especially from a number of central banks (The People’s Bank of China chief among them), has been robust in recent years.7 According to the May trade data from StatCan, gold exports were a key driver of Canada’s rise in total exports, as shown in Exhibit 4.

Contribution to the monthly change in exports, by product, May 2025, monthly change in millions of current dollars. Calculated on a balance-of-payments basis and seasonally adjusted. Source: Statistics Canada, SEI.

While Canada is a modern, services-dominated economy, industrial activity and exports still play meaningful roles. If global gold demand persists, it could provide the Canadian economy a welcome offset to trade pressures threatened by a slower-growing, higher-tariff world. And if government fiscal impulses unfold in much of the world as we expect, perhaps we could see a rebound or at least some steadiness of energy demand and prices as well (though judging by the very short-lived runup of crude oil prices in response to the Iran-Israel-U.S. conflict, markets still view energy supplies as plentiful).

While these two observations won’t turn Canada’s economic performance around by themselves, they do offer a couple of silver linings to an otherwise concerning trade and export outlook.

What to do while we’re waiting

What should an investor do while waiting for clarity around the many risks facing economies and markets today? Perhaps the most important thing to do is remember that investing is all about assuming risk and hopefully being compensated fairly (or better!) for it. As long as the degree of risk assumed is well-suited to an investor’s financial objectives and constraints, and the bedrock principles of diversification are adhered to, one can observe the unfolding geopolitical environment with some emotional detachment, however chaotic it might get.

Definitions

Consumer price index (total CPI): The Consumer Price Index (CPI) is an indicator of changes in consumer prices experienced by Canadians. It is obtained by comparing, over time, the cost of a fixed basket of goods and services purchased by consumers. The CPI is widely used as an indicator of the change in the general level of consumer prices or the rate of inflation. Since the purchasing power of money is affected by changes in prices, the CPI is useful to virtually all Canadians.

Core inflation measures: The prices of certain CPI components can be particularly volatile. These components, as well as changes in indirect taxes such as GST, can cause sizeable fluctuations in total CPI. In setting monetary policy, the Bank seeks to look through such transitory movements in total CPI inflation and focusses on “core” inflation measures that better reflect the underlying trend of inflation.

CPI-trim: CPI-trim is a measure of core inflation that excludes CPI components whose rates of change in a given month are located in the tails of the distribution of price changes. This measure helps filter out extreme price movements that might be caused by factors specific to certain components. In particular, CPI-trim excludes 20 per cent of the weighted monthly price variations at both the bottom and top of the distribution of price changes, and thus it always removes 40 per cent of the total CPI basket. These excluded components can change from month to month, depending on which are extreme at a given time. A good example would be the impact of severe weather on the prices of certain food components. This approach differs from traditional a priori exclusion-based measures (e.g. CPIX), which every month omit a pre-specified list of components from the CPI basket.

CPI-median: CPI-median is a measure of core inflation corresponding to the price change located at the 50th percentile (in terms of the CPI basket weights) of the distribution of price changes in a given month. This measure helps filter out extreme price movements specific to certain components. This approach is similar to CPI-trim as it eliminates all the weighted monthly price variations at both the bottom and top of the distribution of price changes in any given month, except the price change for the component that is the midpoint of that distribution.

Important Information

SEI Investments Canada Company, a wholly owned subsidiary of SEI Investments Company, is the Manager of the SEI Funds in Canada.

The information contained herein is for general and educational information purposes only and is not intended to constitute legal, tax, accounting, securities, research or investment advice regarding the Funds or any security in particular, nor an opinion regarding the appropriateness of any investment. This information should not be construed as a recommendation to purchase or sell a security, derivative or futures contract. You should not act or rely on the information contained herein without obtaining specific legal, tax, accounting and investment advice from an investment professional. This material represents an assessment of the market environment at a specific point in time and is not intended to be a forecast of future events, or a guarantee of future results. There is no assurance as of the date of this material that the securities mentioned remain in or out of the SEI Funds.

This material may contain "forward-looking information" ("FLI") as such term is defined under applicable Canadian securities laws. FLI is disclosure regarding possible events, conditions or results of operations that is based on assumptions about future economic conditions and courses of action. FLI is subject to a variety of risks, uncertainties and other factors that could cause actual results to differ materially from expectations as expressed or implied in this material. FLI reflects current expectations with respect to current events and is not a guarantee of future performance. Any FLI that may be included or incorporated by reference in this material is presented solely for the purpose of conveying current anticipated expectations and may not be appropriate for any other purposes.

Information contained herein that is based on external sources or other sources is believed to be reliable, but is not guaranteed by SEI Investments Canada Company, and the information may be incomplete or may change without notice. Sources may include Bloomberg, FactSet, Morningstar, Bank of Canada, Federal Reserve, Statistics Canada and BlackRock.

There are risks involved with investing, including loss of principal. Diversification may not protect against market risk. There may be other holdings which are not discussed that may have additional specific risks. In addition to the normal risks associated with investing, international investments may involve risk of capital loss from unfavourable fluctuation in currency values, from differences in generally accepted accounting principles or from economic or political instability in other nations. Emerging markets involve heightened risks related to the same factors, in addition to those associated with their relatively small size and lesser liquidity. Bonds and bond funds will decrease in value as interest rates rise.

Index returns are for illustrative purposes only, and do not represent actual performance of an SEI Fund. Index returns do not reflect any management fees, transaction costs or expenses. Indexes are unmanaged and one cannot invest directly in an index. Past performance does not guarantee future results.

Commissions, trailing commissions, management fees and expenses all may be associated with mutual fund investments. Please read the prospectus before investing. Mutual funds are not guaranteed, their values change frequently and past performance may not be repeated.